Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, arguably the most famous painting in the history of Western art, was stolen from the Louve Museum in Paris at 7:20 on 21 August 1911. As the museum’s night security guard was leaving the building, a mustachioed man in a mac jumped out of a cleaning cupboard, cut the painting loose from its frame, rolled up the canvas and simply hid it under his jacket. The thief was let out of the building by an innocent handyman who was making some morning repairs, hailed a taxi and disappeared in the morning traffic. Surprisingly, nobody spotted the Mona Lisa’s disappearance until Tuesday: the museum was closed on Mondays, and security staff thought that the painting had been removed to be photographed. Indeed, the museum’s first response to the disappearance was: “When beautiful women are not with their lover, they are posing for their photographer!” But it soon became obvious that nobody was quite sure of where the painting was. The police inspected the museum and interrogated the security guards, all to no avail. Meanwhile, more and more curious visitor were queuing up in front of the empty frame: it was then that the Mona Lisa became the tourist sensation it has been ever since.

Discovering the thief proved surprisingly difficult for such a high profile case. Indeed, political and personal disagreements resulted in several fake accusations which shook the contemporary cultural world. For example, a deserted lover wrongly accused poet Guillaume Apollinaire of having bought several antique statuettes stolen from the Louvre. The case eventually solved itself: in December 1912, Florentine antiquarian Alfredo Geri received an anonymous letter saying: “I have the painting, it belongs to Italy as Leonardo was Italian.” The thief asked for a moderate ransom in return for the artwork. The exchange took place in a modest pension in Florence, now renamed “La Gioconda” to celebrate the important historical moment which quietly took place on its third floor. The identity of the thief was revealed and he was swiftly arrested. His name was Vincenzo Peruggia, a painter-decorator who had emigrated to France. Peruggia was tried in Italy at the same time as the assassination of archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria triggered the First World War. Peruggia’s defense was based on his patriotism, as he was convinced that the painting had reached France after having stolen by Napoleon during his invasion of Italy (actually, it is almost certain that Leonardo himself took the painting to France when he settled at the Court of King François I in 1516/17). His arguments were rather successful in those warmongering days: he was condemned to one year and fifteen days in prison, of which he only served seven and a half months. He later started a family and opened a paint shop in the north west of Italy, without ever revealing if his crime had been orchestrated by some greedy foreign collector or enterprising forger, for example the Argentinian conman and self-styled Marquis Eduardo de Valfierno.

Reference: Stefano Bucci, ‘Furto della Gioconda, cent’anni di mito’ Corriere della Sera, 8 August 2011, http://www.corriere.it/cultura/11_agosto_19/bucci-furto-gioconda-mito_18b7675c-c1a5-11e0-9d6c-129de315fa51.shtml?refresh_ce-cp; Martin Kemp, “Leonardo da Vinci,” Grove art Online, Oxford University Press, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T050401.

Mona Lisa (La Gioconda), c. 1503-5, oil on panel, 77 x 53 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Source: Web Gallery of Art.

Mug shot of Vincenzo Peruggia in 1909

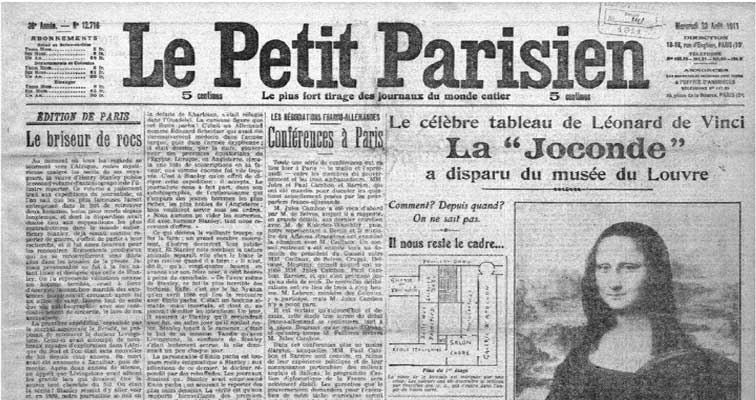

Le Petit Parisien newspaper reports the theft of the Mona Lisa, 23 August 1911

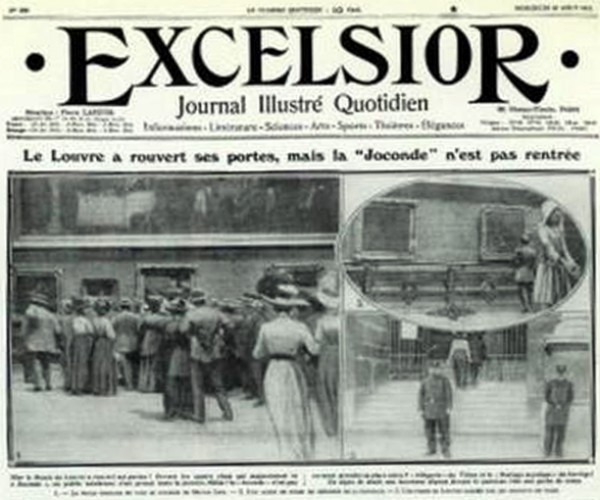

The Excelsior newspaper publishes pictures of the growing crowds in front of the Mona Lisa’s empty spot, 23 August 1911

Le Petit Parisien celebrates the recovery of the Mona Lisa, 14 December 1913

The Excelsior reconstructs the crime, January 1913