Italian photographer Mario Giacomelli died in Senigallia, on Italy’s Adriatic coast, on 25 November 2000.

Born in the same town in 1925, Giacomelli started working as apprentice in a printing house when just twelve years old. He did not receive an formal artistic training, but encountered photography casually during a trip to Rome with his fiancée in 1950. In the following years, the artist explored contemporary photography through magazines and entered Senigallia’s artistic scene, becoming a founding member and treasurer of its photographic association, MISA. At the same time, he started developing and printing his own photographs himself, and took part in the first group exhibitions and competitions.

The MISA group and its parent art movement, La Bussola(the compass), were inspired by the aesthetic theories of Benedetto Croce(1866-1952), an idealist philosopher, historian and public figure. For Croce, artworks were mental images, ideas to be comprehended through feeling rather than objects. As a result, he initially perceived the appreciation of art as a private emotional experience, although he later affirmed the universality of the artwork, and the close connection between art, humanity, and morality. As interpreted by mid-twentieth century Italian photographers, such ideas translated into studied photographs portraying universal themes such as Motherhood, Farm Life, and Unemployment with soft contrasts of light and shade.

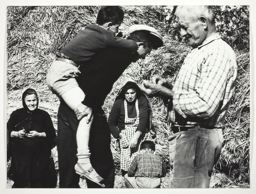

Giacomelli followed this aesthetic until 1957, when he exposed his first series of photographs, Vita d’Ospizio (Life in the nursing home), at the inaugural Photography Biennial in Venice. Featuring open-eyed and even crude images of life and death in the hospice, the images were miles away from the ‘lyrical realism’ popular at the time. In the following years Giacomelli perfected his moving and harsh style during trips to the sanctuaries of Lourdes and Loreto. although relatively isolated in the contemporary Italian art world, such high-contrast, low-fidelity images recall the approach of contemporary photographers further afield, for example William Klein, Werner Bischof, Robert Frank, and Pierre Verger.

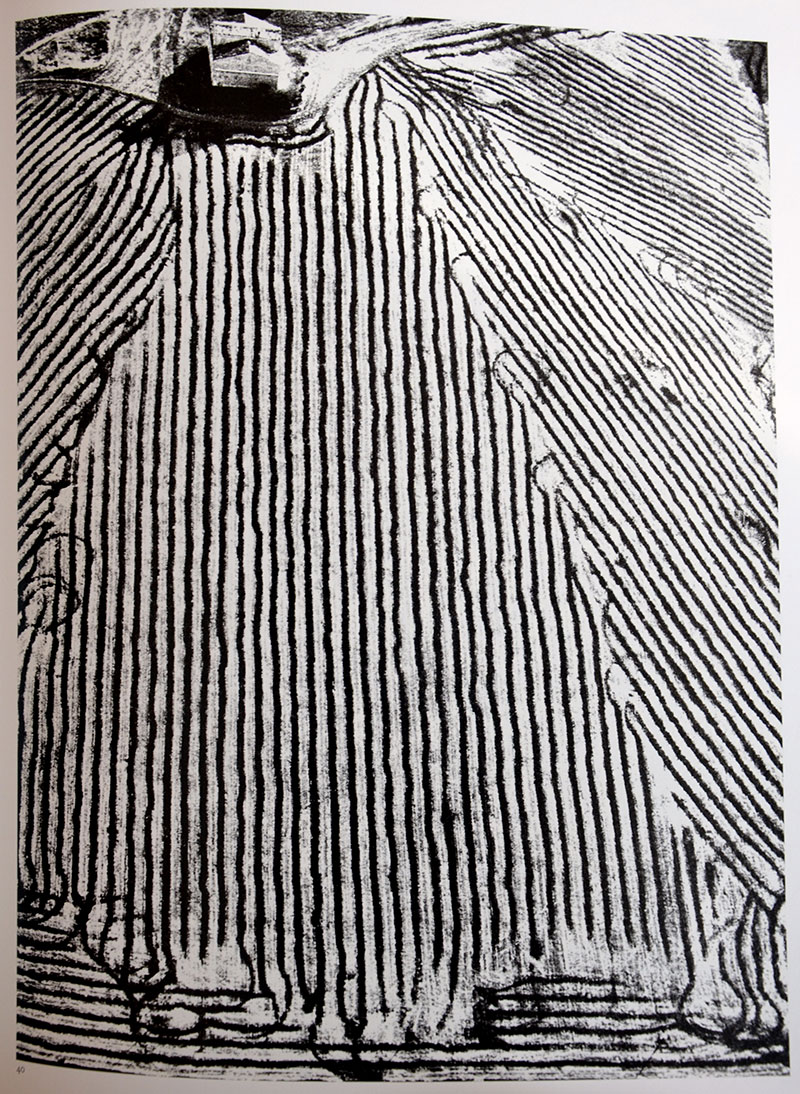

Inspired by his supporter and teacher, Luigi Crocenzi, Giacomelli turned to photo-reportage and especially photo-narrative, realizing series of photographs inspired by literature of poetry. In this vein, the artist followed a local couple for several months (Un uomo, una donna, un amore, ‘A Man, a Woman, a Romance,’ 1960-61), spent almost a year with a patriarchal family of farmers (La buona terra, ‘The Good Earth,’ 1964-66), and even portrayed the most off-guard and carefree moments of theology students at Senigallia’s seminary (Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto, ‘I Have No Hands that Caress My Face,’ 1961-63), causing a scandal in the local Church. He also engaged with classical poetry, as in the series Caroline Branson (1967-1973), inspired by Edgar Lee Master’s Spoon River Anthology. Crocenzi also promoted Giacomelli’s works abroad, with exhibitions in France, Spain, and the United States, where the MOMA featured the artist in his landmark exhibition The photographer’s eye (1964).

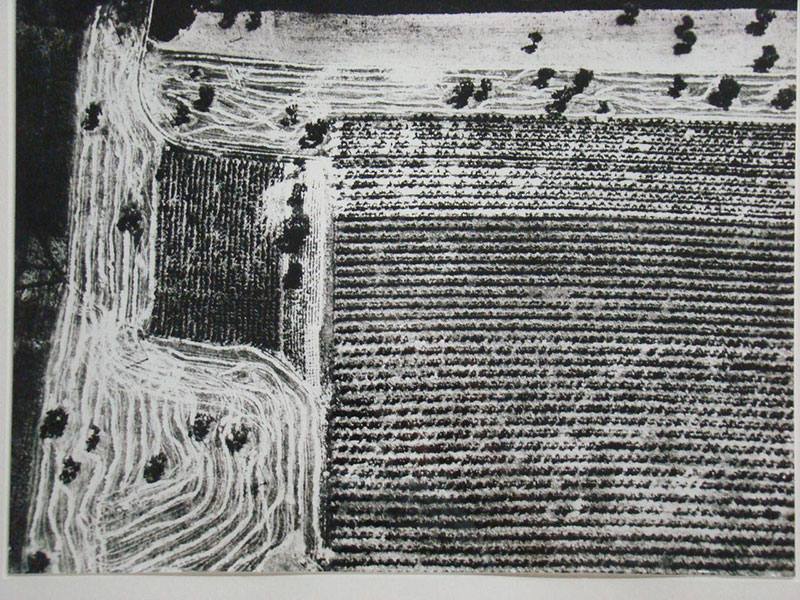

Giacomelli reached his widest international success in the 1970s. Afraid of flying, he initially developed images taken by friends in exotic locales such as Morocco and India. Later on, he turned fear into force with the breathtaking aerial landscapes which became the signature style of his mature production. Accurately documenting a changing landscape, Giacomelli’s photographs of his native region were used as analytical evidence by contemporary social historian Sergio Anselmi. Yet they were also open to conceptual and atmospheric interpretations, as at the 1978 Venice Biennal. Here Giacomelli turned a whole room into a single artwork, showing 17 large-scale landscapes in ascending and then descending order on the walls, and two aerial photographs surrounding a plot of real soil on the floor.

The photographer’s final consecration as a great Italian artist was a large-scale retrospective exhibition held in Parma in 1980 and accompanied by a wide-ranging critical catalogue featuring more than 500 artworks. In the following years, Giacomelli increasingly turned to the illustration of poetry, often in a melancholic spirit. Yet he also worked for leading companies such as Levi’s, Fiat and Illy, realizing convincing promotional images without compromising on his original photographic style.

You can read more about this artists and see more pictures on Giacomelli’s website and archive.

Reference: Marco Andreani, ‘GIACOMELLI, Mario,’ Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (2016).

Lourdes, France, 1957/58, gelatin silver print, 29.4 x 39.7 cm. Chicago: Art Institute, gift of the Mattis Family, 1987.368.3.

La Buona Terra, 1966, gelatin silver print, 30.5 x 40.3 cm. Chicago: Art Institute, gift of Jed Fielding, 1994.668.

Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto, gelatin silver print, 30.5 x 40.6 cm. Rivoli: Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, purchased with the contribution of BNL Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, 1993.

Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto, gelatin silver print, 30.5 x 40.6 cm. Spillimbergo: CRAF.

Landscapes, from Fosco Lucarelli, ‘On Being Aware of Nature,’ http://socks-studio.com/2014/09/15/on-being-aware-of-nature-mario-giacomellis-landscapes/

Verrá la morte e avrá i tuoi occhi (Death will Come and it will Have Your Eyes), title taken from a poem by Cesare Pavese, 1940/95, gelatin silver print, 40.4 x 30.3 cm. Chicago: Art Institute, gift of Jed Fielding, 1995.298.