Much is in dispute about the history of The Etruscan School (Scuola etrusca), but 28 January 1883 was the day when the group of Italian and English landscape painters began a yearlong formal association in Rome. Beyond that, even the name of the group was never widely accepted and came to refer retrospectively to the landscapes that artists in this circle painted and exhibited together from the 1860s until around 1910. Under the influence of Giovanni (Nino) Costa they revived the tradition of landscape painting that derived from Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin and that Thomas Jones, Pierre Henri Valenciennes, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot had explored.

The aesthetic principles that determined the nature of the paintings of the Etruscan school were first discussed by Costa with George Hemming Mason and Frederic Leighton, whom he had met in 1852 and 1853 respectively. From 1877 Costa exhibited landscapes at the Grosvenor Gallery, London, in the company of George James Howard, Matthew Ridley Corbet, Edith Corbet, William Blake Richmond, Edgar Barclay, and Walter Maclaren; and the Italians Gaetano Vannicola (1859–1923) and Napoleone Parisani (1854–1932). These painters, with the addition of Norberto Pazzini (1856–1937), were the original members of the Etruscan School.

Their style of painting is characterized by breadth of handling and a fondness for the subdued tonalities of panoramic distances. Costa instructed his followers that the purpose of the landscape artist is to evoke and describe the emotions and affections felt for his native land; sentiment is to be regarded as the most important element in a painting: “…the study which contains the sentiment, the divine inspiration, should be done from nature,” he is recorded as saying. Then: “…from this study the picture should be painted at home, and, if necessary, supplementary studies be made elsewhere.” From 1888 the members of the group transferred their allegiance from the Grosvenor Gallery to the New Gallery, London, exhibiting there until 1909.

Among the artists who remained in Italy, Napoleone Parisani left the largest body of work and worked in a variety of other styles, having trained in drawing and rendering at the Academy in Rome throughout the 1880s. Fascinated by the art of Poussin and the Fontainebleau School of Landscapeists, Parisani also accepted commissions and experimented with religious subjects. One such interesting side project is an altarpiece for the Church of Santa Maria Extra Moenia in Prossedi called Strammetta. The triptych was created between 1902 and 1905 and exhibited at the VI Venice Biennale.

Reference: Jane Turner. The Grove Dictionary of Art. From Renaissance to Impressionism: Styles and Movements in Western Art, 1400-1900. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2000; p. 96.

Napoleone Parisani. Hillside with Olive Trees, c. 1890. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

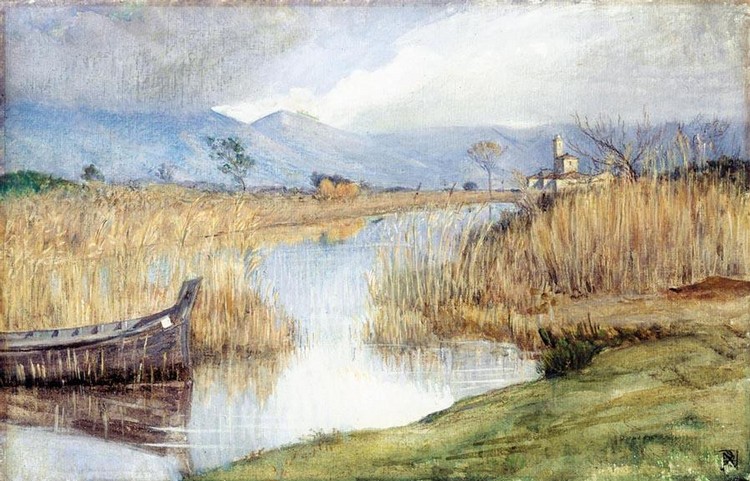

Napoleone Parisani. Marshes, c. 1890. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Napoleone Parisani. Paesaggio fluviale con ponte e torre, c. 1890. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Napoleone Parisani. Veduta del Tevere, c. 1888. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Norberto Pazzini, The Tiber, c. 1886. Photo: The Leicester Galleries.

Norberto Pazzini, Untitled, c. 1886. Alessio Ponti Gallery, Rome.

Napoleone Parisani. Altarpiece, c. 1902-1905.

Further Reading: Christopher Newall. The Etruscans: Painters of the Italian Landscape, 1850-1900. Stoke on Trent: Stoke on Trent City Museum and Art Gallery, 1989.