Lorenzo di Credi (Lorenzo d’Andrea d’Oderigo) was born in Florence in about 1459 and was the son of a goldsmith. The polymath, Giorgio Vasari described him as, “a young man of beautiful intellect and excellent character,” who was tutored in artistic praxis by Andrea del Vercocchio.

Vasari then goes on to reveal that, “having Pietro Perugino and Leonardo da Vinci as his companions and friends, although they were rivals, he set himself with all diligence to learn to paint. And since Lorenzo took an extraordinary pleasure in the manner of Leonardo, he contrived to imitate it so well that there was no one who came nearer to it than he did in the high finish and thorough perfection of his works, as may be seen from many drawings that are in our book, executed with the style, with the pen, or in water-colours, among which are some drawings made from models of clay covered with waxed linen cloths and with liquid clay, imitated with such diligence, and finished with such patience, as it is scarcely possible to conceive, much less to equal.”

Giorgio Vasari also maintained that Lorenzo di Credi was, “beloved by his master,” and although the cinquecento writer was often prone to exaggeration, in this case he appears to have been extremely accurate. According to the will of Andrea del Vercocchio, which was drawn up shortly before his death in 1488, Lorenzo was not only named as his executor, but the inheritor of his workshop and many of his worldly goods. Whilst dying in Venice, Verrocchio dictated the following, “… and first, I constitute the executor of this my will Lorenzo [di Credi] son of Andrea de Orderich, Florentine painter… I leave to the said executor Lorenzo all bronze, tin pophery, and furniture and furnishings in my house, which are all in Florence and also a pair of bellows… I leave to him all furnishings, clothing, bed and all other furniture of mine that I have in Venice.’ And apart from several properties and items that, “I leave to my brother Tomasso… the rest of my goods, rights and shares present and future, wherever located, I give and leave to the said Lorenzo.’

Despite his inheritance and elevation to Master of the bottega, during the late 1480s, Lorenzo, although perhaps reasonably occupied with small commissions, did not appear to be able to gain or retain the more lucrative, large projects that had historically come into Verrocchio’s workshop. For instance on 3 October 1488 Credi signed a contract to complete the Pistoia monument, a commission originally secured by his deceased master, yet by 1514 it was still unfinished; similarly Credi was not invited back to Venice to complete the equestrian statue begun by Verrocchio and by January 1489 the Venetians had allowed the exiled Alessandro Leopardi to return in order to complete it. Credi did, however, manage to take on other artistic commissions, including a series of small paintings for the Convento di San Gaggio.

On 12th January 1537, Lorenzo died and according to his last will and testament, he named the lay confraternity of the Buonomini di San Martino (otherwise known in Florence as the Procurators of the Ashamed Poor) his “universal heirs.” Furthermore, “as soon as [was] possible after Lorenzo’s death they [the confraternity, would] attend to the sale of Lorenzo’s furniture and goods and exchange everything for cash.” The proceeds of this sale would then go on to benefit the city’s morally upstanding individuals, who had fallen upon hard times, and for whom it would not be fitting to openly beg.

References: Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite de’ Piú Eccelenti Architetti, Pittori, et Scultori Italiani, da Cimabue Insino a’ Tempi Nostri, Florence, 1550.

Gigetta D. Regoli, Verrocchio, Lorenzo di Credi, Francesco Simone di Ferrucci, Milan, 5 Continents Editions, 1966.

Wilhelm R. Valentiner, “Leonardo as Verrocchio’s Coworker.” In The Art Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 1, 1930, pp. 42-89.

Dario A. Covi, “New Documents Concerning Andrea del Verrocchio.” In The Art Bulletin, vol. 48, no. 1, 1966, pp. 97-103.

Günter Passavant, (trans. Katherine Watson), Verrocchio: Sculptures, Paintings and Drawings, London, Phaidon Press, 1969, p. 9.

G. Gaye, Carteggio Inedito D’Artisti Dei Secoli XIV XV XVI, Documenti di StoriaItaliana III, pp. 367 & 372.

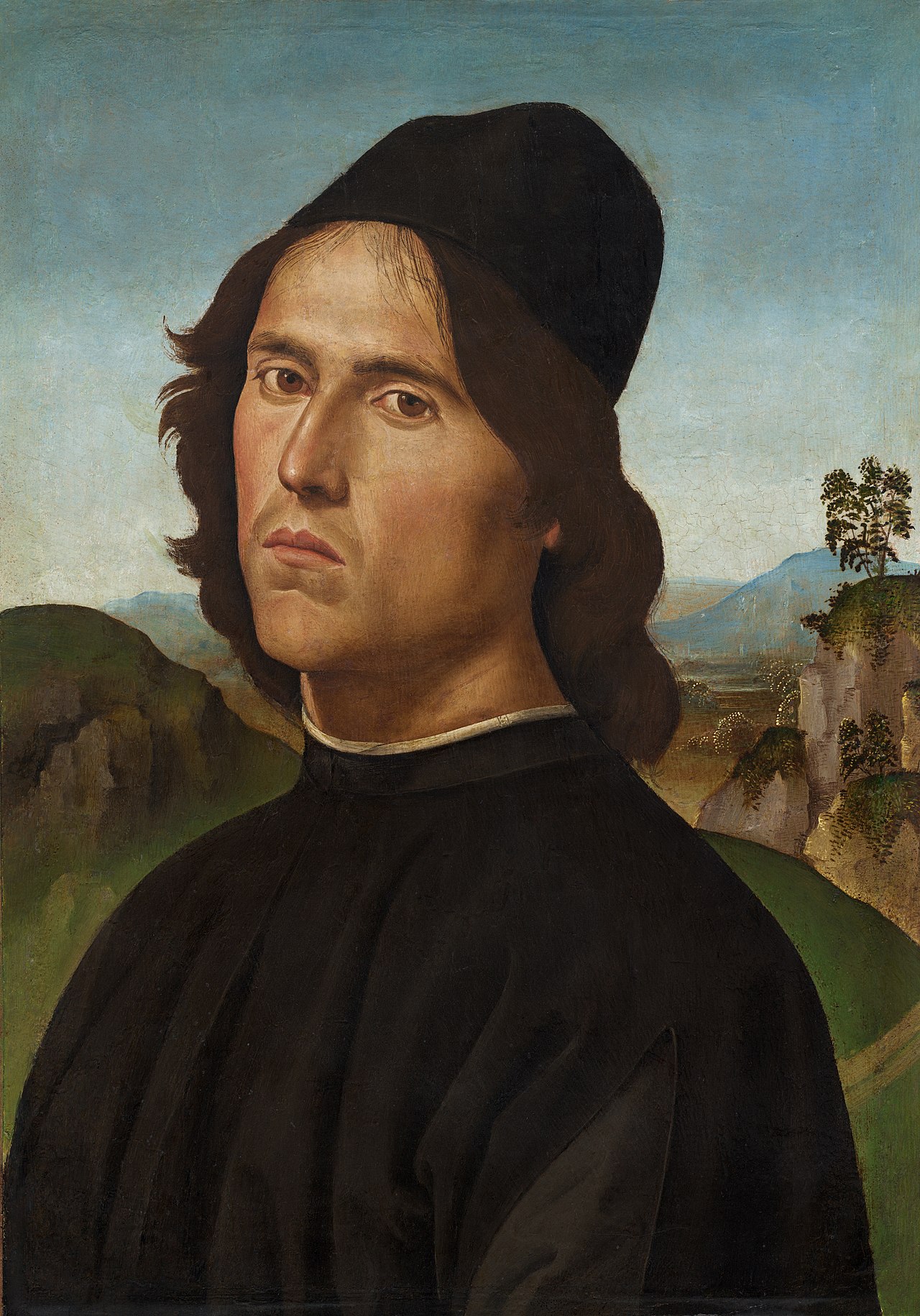

Images: Pietro Perugino, Portrait of Lorenzo di Credi, c.1488. tempera on wood transferred to canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Public domain image.

Portrait of a Young Woman, 1490-1500, oil on wood, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Wikimedia Commons.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci, 1474-8, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Public domain image.

Jesus and the Samaritan, between 1475 & 1500, oil on wood, Museo il Cenacolo di Fuligno, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

Noli me Tangere, between 1475 & 1500, oil on wood,Museo il Cenacolo di Fuligno, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

Annunciation, between 1475 & 1500, oil on wood, Museo il Cenacolo di Fuligno, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

The workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio, Giving Food to the Hungry and Drink to the Thirsty, 1486-1490, fresco, Oratorio dei Buonomini di San Martino, Florence. Image gifted to the author. © Antonio Quattrone.

Further Reading: Bernard Degenhart, “Drawings by Lorenzo di Credi.” In The Burlington Magazine, vol.57, no. 328, 1930, p. 15.

Roger Fry, “A Tondo by Lorenzo di Credi.” In The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin,vol. 4, no. 10, 1909, p. 187.

Francis W. Kent, “Lorenzo di Credi, his patron Iacopo Bongianni and Savonarola.” In The Burlington Magazine, vol.125, no. 966, 1983, p. 540.

L. Planiscig, Andrea del Verrocchio, Vienna, 1941, pp. 40-43.

Posted by Samantha Hughes-Johnson.