The July 24, 1944 edition of LIFE magazine includes a photo-essay about the destruction of Italian art during World War II. Photojournalist George Silk documented the destruction of churches in three Campanian cities – Capua, Naples, and Benevento. The article, entitled “War Ravages Italy’s Art: Allies Try to Save Great Relics” addresses the conundrum faced by General Eisenhower and his commanders throughout their invasion of Europe: “…which is more precious: life itself or the living cultural traditions that give life much of its meaning.” Collateral damage was inevitable, but Silk’s photos underscored the salvage of church art and architecture that was already taking place. The article also makes a contemporary reference to the wartime art specialists we now know as monuments men:

The British and U.S. governments have set up a group of experts to carry on the work of art preservation. The experts have prepared maps for bombing missions, carefully plotting the location of art treasures so that the bombers can avoid any unnecessary destruction. Once a town is captured, the art experts quickly move in to minimize damage. They erect scaffoldings to support shaken walls and ceilings, put up temporary roofs to protect interiors from rain and weather, gather all rubble together so it can be sifted for valuable fragments that can be used later to reconstruct damaged works. They have already helped compile a record of every important movable piece of Italian art, including all of the Nazi loot. This list will help to return to the pillaged towns many of their priceless paintings and sculptures. (57)

Reference: “War Ravages Italy’s art: Allies Try to Save Great Relics.” Life Magazine, July 24, 1944. 56-63.

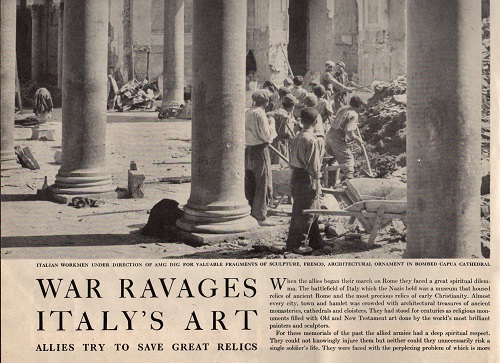

Italian workmen under allied Military Government (hereafter AMG) dig for valuable fragments of sculpture, fresco, and architectural ornament in the bombed Capua cathedral.

Benevento Cathedral door before bombing, the upper part showing scenes from the New Testament and panels portraying Benevento bishops.

After the bombing, the cathedral door fragments were spread on the floor by a Benevento priest who is trying to piece them together. He has placed rosettes in the spots where panels are missing.

The cathedral of Capua is gutted. The altar is now part of rubble in the foreground. AMG officials sifted rubble for fragments of a 13th-century Madonna, an 11th-century illuminated manuscript, frescoes, and statuary.

Under the archway of Capua cathedral, workmen directed by the AMG have set aside pieces of church sculpture (left) and the capitals of overturned columns which were salvaged from the rubble are lying at the right.

Harold Johnson is a former forensic DNA analyst and a freelance scholar and consultant. His experience in museum studies and art history includes graduate work at The University of Chicago and continuing education at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, the Museu Nacional de Arqueologia in Lisbon, the Association for Research into Crimes against Art postgraduate certification program in Art Crime and Cultural Heritage Protection, and the Tulane-Siena Institute for International Law, Cultural Heritage & the Arts.