On 30 October 1500, the Signoria of Venice granted the Nuremberg merchant Anton Kolb a printing privilege for Jacopo de’ Barbaris View of Venice. A precursor of modern copyright, this privilege ensured that copies of the View printed by Kolb would be legally protected from counterfeits for a period of four years. This is an early instance of the legislation, which had first appeared in Venice in 1469.

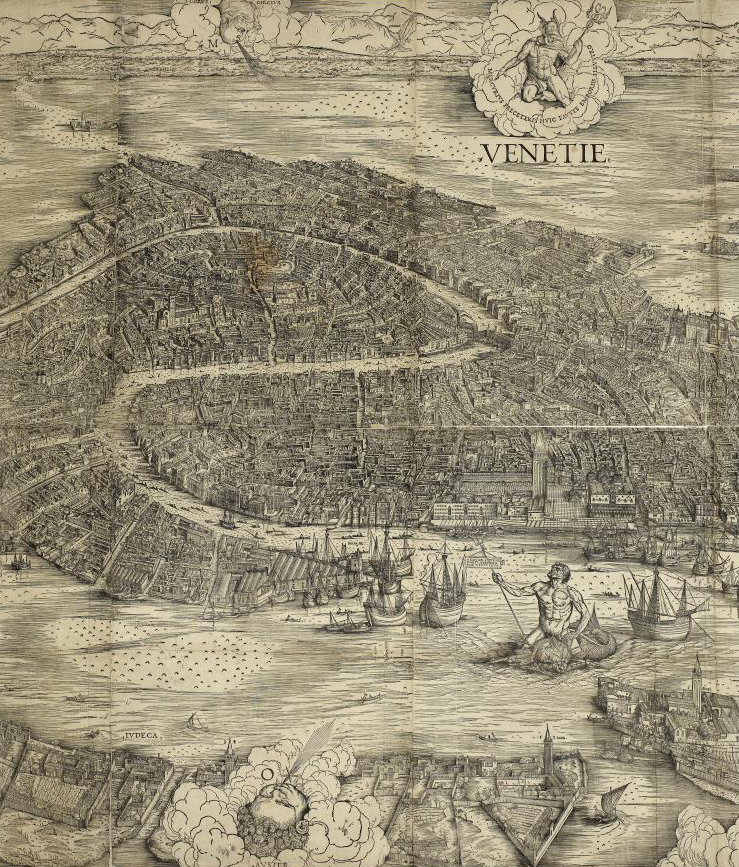

Printed from six blocks on six sheets of joined paper, Jacopo de’ Barbaris woodcut precisely records the appearance of Venice at the beginning of the sixteenth century. You can travel through its streets and squares by watching this music and theater performance by the early music group ¡Sacabuche!.

The map is known in two states: the first version, dated to 1500, shows the Campanile in Piazza San Marco with a temporary flat roof built after a fire in 1489; the second takes account of the restoration of the roof which had taken place in 1511-4. Extremely detailed and printed with exacting care, the map is 4 meters wide. At a cost of three ducats, it was a luxury item intended for serious print collectors. Nevertheless, scientific precision was nuanced to create mythological and cultural associations. The Roman gods Neptune and Mercury were represented above and below the city, evoking their protection on the seafaring merchant center. Moreover, the overall shape of the city was deformed to resemble a dolphin, an animal associated with Venus, but also with speed, fortune, musical, harmony, and the Christian resurrection of the soul. Despite these positive associations, a mystery remains: why was the map’s publication allowed, and even officially supported by the Republic of Venice, despite its potential usefulness to an aggressor?

Born in Venice around 1460–70, Jacopo de Barbaris probably trained with Alvise Vivarini in Venice in the 1490s. After producing several prints in Venice, he entered the service of Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, and moved to Wittenberg in 1503. He became the first Italian Renaissance artist of note to travel to Germany and the Netherlands. Only a dozen paintings attributed to him survive, among which Still-life with a Dead Partridge, a trompe l’oeil probably executed for one of the Saxon dukes’ palaces. Dated to 1504, this panel is the earliest still-life painting of the Renaissance. The painter’s creativity was much appreciated by his contemporaries: Albrecht Dürernoted in a letter of 1506 that “Anton Kolb swears an oath that no better painter lives on earth than Jacob.”

Jacopo de’ Barbari, View of Venice, woodcut, first state, c. 1500. London: British Museum.

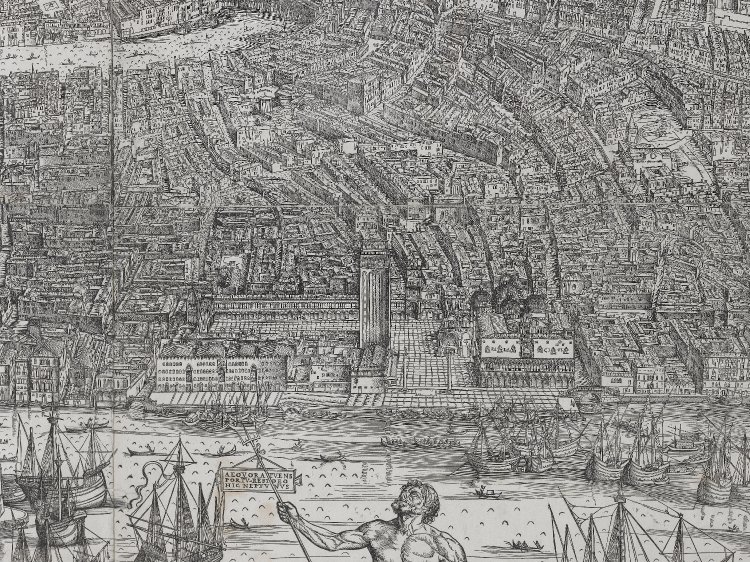

Detail of S. Marco Square, View of Venice, woodcut, first state, c. 1500. London: British Museum.

Jacopo de’ Barbari, View of Venice, woodcut, second state, after 1514. London: British Museum.

Detail of Jacopo de’ Barbari, View of Venice, woodcut, second state, after 1514. London: British Museum.

Jacopo de’ Barbari, Still-Life with Partridge and Iron Gloves, oil on panel, c. 1504. Munich: Alte Pinakothek.

References: Jay a. Levenson. “Barbari, Jacopo de’.” Grove Art Online. Oxford art Online. Oxford University Press, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T006234; Howard, Deborah. “Venice as a Dolphin: Further Investigations into Jacopo de’ Barbari’s View.” Artibus et Historiae 18, no. 35 (1997).

Further Reading: Bellini, Giorgione, Titian and the Renaissance of Italian Painting, online exhibition resource, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2006/venice/fullscreens/191-103.shtm