On 28 May, 585 BCE, a solar eclipse occurred. The astronomical phenomenon had been calculated and predicted by the Greek philosopher and scientist Thales, and because of the certainty of his observations and notes, it is one of the cardinal events of the ancient world from which other dates can be calculated. The seeming magical and rare nature of the eclipse and its association with the divine naturally aligned the brief disappearance of the sun with art and religion.

The solar disc behind the head of the Ephesian Artemis is thought to represent the eclipse, as the four lions to her right and left carry the sun across the sky. The celestial affiliation connects this Artemis to the Roman Diana though unlike the maiden Diana the Ephesian goddess was one of fertility and fruitfulness. However, the life-size Roman statues of Artemis Ephesia do not display rows of breasts but instead a sort of garment padded with seeds, corn, and pendants wound with bands of ribbon.

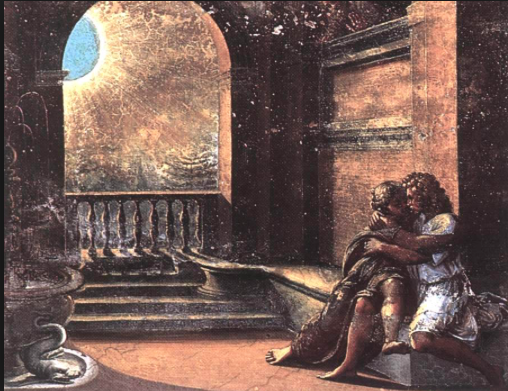

In his Annunciation to the Shepherds in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, Taddeo Gaddi represented divine radiance using light effects that he had seen during the eclipse of 16 July 1330 — a viewing that left him partially blind. Raphael based the eerie corona in the scene of Isaac and Rebecca Spied on by Abimelech on the eclipse of June 1518, which he also, though without injury, had witnessed himself. The painting interprets Genesis 26:8 in which Isaac — who called his wife, Rebecca, his sister – embraces Rebecca while Abimelech, king of the Philistines, spies on the couple from his window. The eclipse makes a metaphor of the impenetrability of the darkness.

Subsequent appearances of the eclipse in Italian art are also interpretive, such as landscape painter Ippolito Caffi’s oil painting View of Venice with the Eclipse of 8 July 1842, which depicts one-quarter of the sky brightly lit and three-quarters of it dark, a scientific and observational inaccuracy that nonetheless does show an eclipse as a process involving dynamic changes in light.

Architect Gaetano Pesce’s drawings of the Period of Contaminations, Housing Unit for Two People, are two works designed for his installation in The Museum of Modern Art’s 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape. Pesce’s work presented a third-millennium archeologist’s discovery of an underground southern alpine city into which people had retreated to avoid the imagined radiation from an eclipse. Ettore Sottsass used The Planet as Festival series to depict the eclipse as harbinger of a utopian land where all of humanity would be free from work and social conditioning. In his futuristic vision goods are free, abundantly produced, and distributed throughout the globe. The Planet as Festival drawings are black-and-white studies for hand-colored lithographs. They depict such “super-instruments” for entertainment as a monolithic dispenser for incense, drugs, and laughing gas set in a campground, rafts for listening to chamber music on a river, and a stadium to watch the eclipse.

Reference: Jay M. Pasachoff and Roberta J. M. Olson. “Art of the Eclipse: As the Next Solar Eclipse Approaches … How Artists from the Early Renaissance Onwards Have Interpreted the Phenomenon.” Nature. 17 April 2014. Vol. 508 (7496), p. 314 (2).

Ippolito Caffi, View of Venice with the Eclipse of 8 July 1842, c. 1843. Wikimedia Commons.

Antoine Caron, Dionysius the Areopagite Converting the Pagan Philosophers, c. 1570. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Gaetano Pesce, The Period of Great Contaminations: Housing Unit for Two People, axonometric section views, 1971-1972. Gouache, watercolor, and graphite with scoring on paper. The Museum of Modern Art, Architecture and Design Collection, Nrs. 1221.2000; 1222.2000.

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Study for Rafts for Listening to Chamber Music, 1972-73. The Museum of Modern Art, Architecture and Design Collection, Nr. 1297.2000.

Ephesian Artemis, Statue (alabaster, gilt; bronze head, hands, feet), Second Century. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, Nr. 6278. Roman copy of a Hellenistic original. Formerly in the Farnese Collection.

Half-Moon Plaque with Dionysos, Ariadne, and Eros, c. 350, Byzantium. The Walters Art Museum Museum, Nr. 71.1127.

Tadeo Gaddi, Annunciation to the Shepherds, c. 1335. Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence.

Raphael and his workshop, Isaac and Rebecca Spied upon by Abimelech, 1518–19. The Vatican Palace.

Further Reading: Elly Rachel Truitt. Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Mary D. Garrard. Brunelleschi’s Egg: Nature, Art, and Gender in Renaissance Italy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Thank for this article! Well researched and written with passion. History can teach us if we decide to learn.

Thank you for your response Danielle. It’s wonderful to receive such positive feedback.