Barbarian Burial Sheds Light on Legion’s Legends

Roman writers and artists often made the “wild and savage” “barbarians” of Germania the subject of their historical reconstructions and commemorative stonework. Still, we know very little about the battle capability of the Germanic tribes who managed to sometimes successfully hold of the Roman Legions. The few known battle sites in Germany itself (most notably centered around the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest) contain very little in the way of well-preserved remains, and questions abound about how large “barbarian” armies actually were and how they were organised.

Archaeologists working in Denmark may now be able to shed some surprising light on this mystery. Researchers working in a sprawling 185-acre wetland have uncovered 2,000-year-old human remains that are challenging traditional ideas about “barbarian” warfare in northern Europe. The research, which was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also provides a unique look at how Germanic tribes memorialised their battles, in stark contrast to their Roman counterparts.

Although they battled Germanic tribes across much of Europe in the First century, Roman armies never made it as far north as southern Scandinavia, and the team didn’t find evidence for direct Roman involvement in this battle.They did learn, however, that the Germans moved the dead to the bog with the specific intent of memorialising those slain in battle, arranging their bones in complicated patterns, grouped in some cases by type.

The northern European tribes were both admired and reviled by the Romans, who incorporated their bearded, trousered iconographies into their own grave markers as well as triumphal arches and towers. There is another reason for the popularity of barbarian motifs in the art of the late Empire. The reigns of Constantine the Great and his sons which saw the foundation of the Christian Empire are meagre in Christian iconography while profane images such as triumphal and military reliefs are numerous.

The object pictured is the supposed sarcophagus of St. Helena, mother of Constantine, who went to the Holy Land and discovered the True Cross during excavations there. The sarcophagus is certainly from her mausoleum in Rome called the Torre di Pignattara. Her remains were removed to Constantinople in 331. The sarcophagus may have been made for Constantius I (surnamed Chlorus, d.306), father of Constantine. Later, the sarcophagus was reused for Pope Anastasius IV (d. 1154) and placed in St. John Lateran.

The Erotes and garlands emphasize the purely triumphal character of the decoration. The porphyry sarcophagus also shows: Roman horsemen driving bound barbarian captives; above right, bust of emperor; three Roman horsemen armed with spears riding victoriously over fallen or captive barbarians; below center, armed soldier squatting, pointing up with finger of left hand; above right and left, busts of emperor (Constantius Chlorus?) and empress (Helena?); top of sarcophagus, Eros holding garland, two winged reclining figures, recumbent lion.

Reference: Kristin Romey. “Thousands of Human Bones Reveal ‘Barbarian’ Battle Rituals.” National Geographic. 22 May 2018.

Column of Marcus Aurelius: The Emperor’s campaigns against the Germanic and Sarmatian barbarians, detail of reliefs from the west side, ca. 181. Piazza Colonna, Rome, Italy. Photo: Art Images for College Teaching.

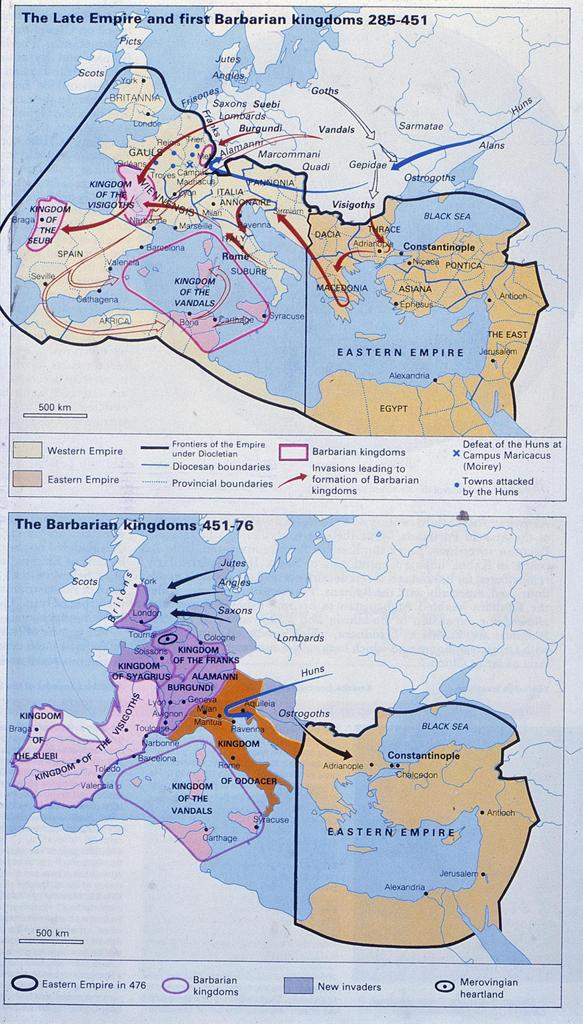

Late Empire and first Barbarian Kingdoms, 285-451. Map: University of California, San Diego.

Europe After the Barbarian Invasions, c. 476. Map: University of California, San Diego.

Arcus Novus of Diocletian Base B, Barbarian captive, c. 294 Photo: University of California, San Diego.

Porphyry sarcophagus, c. 320. Rome: Museo Pio Clementino (Vatican Museum). From cave of La Madeleine (Dordogne).

Silver Cup, showing barbarians receiving clemency from Augustus, c. 10-20. Photo: University of California, San Diego.

Ludovisi battle sarcophagus, relief showing combat between Romans and barbarians, ca. 250. Museo Nazionale, Rome.

Further Reading: Heather Peter. Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

David M. Gwynn. Christianity in the Later Roman Empire: A Sourcebook. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Posted by Jean Marie Carey