Judas Iscariot gained infamy as the disciple of Christ who, according to biblical tradition, betrayed the Lord’s whereabouts to the church’s officials in exchange for thirty pieces of silver. According to the gospel of John (12:6), Judas was the Apostles’ treasurer and a natural thief. John states that, “ [Judas] had the money box [and] he used to take what was put into it.”

Judas’s motivation for betraying Christ is unclear, although Luke (22:3-6) suggests that he was possessed by Satan. Likewise, John (13:27) also mentions that Judas was possessed by the Devil. Matthew (26:14-16) however, adds that Iscariot was also innately avaricious. Furthermore, both Matthew and John suggest that Jesus foresaw the betrayal and that by doing nothing about it, allowed Gods great plan to come to fruition. After all, as Jorges Luis Borges explains, “the treachery of Judas was not accidental; it was a predestined deed which has its mysterious place in the economy of redemption.”

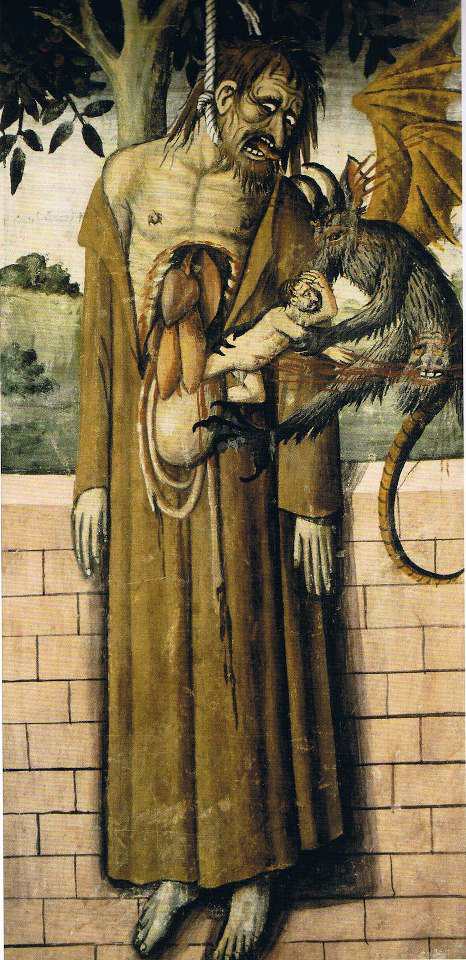

Just as the writers of the gospels could not agree as to why Judas betrayed Christ, church doctrine also provides various scenarios with regard to the manner of Judas’s death. Matthew (27:3-10) suggests that Judas, wracked with guilt, committed suicide by hanging, while Acts 1:18, describe that he “bought a field with the reward of his wickedness; and falling headlong he burst open in the middle and all his bowels gushed out.”

[[MORE]]

Accordingly, in the afterlife, whether Judas was sentenced to eternal damnation because of his betrayal, death by suicide or due to his avarice, he has been portrayed from Dante Alighieri’s time onwards as suffering for his grave sins in the ninth circle of the Inferno. And while hell and damnation were certainly not created by Dante, the images that were produced in order to celebrate and illustrate his Divine Comedy left Medieval and Renaissance viewers with no doubt as to Judas Iscariot’s hideous fate.

Images: Andrea del Castagno, detail from The Last Supper, c.1445, fresco, Sant’Apollonia, Florence.

Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (after Leonardo da Vinci), Head of Judas, 15th century, pencil, black chalk, tempera and watercolour, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg. Wikimedia Commons.

Giotto di Bondone, The Kiss of Judas, 1303-1306, fresco, Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua. Web Gallery of Art.

Giotto di Bondone, Judas Receiving Payment for his Betrayal, 1303-1306, fresco, Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua. Web Gallery of Art.

Fra Angelico, The Kiss of Judas, 1437-1446, fresco, San Marco, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

Giovanni Canavesio, Hanged Judas, early 16th century, fresco, Notre Dame des Fontaines Chapel, La Brigue, Roya Valley, France. Wikimedia Commons.

Coppo di Marcovaldo, Detail of Hell, 13th century, mosaic, Baptistry, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

Pietro Lorenzetti, Hanged Judas, c.1310, fresco, Lower Basilica of San Francesco d’Assisi. Wikimedia Commons.

Attributed to Priamo della Quercia, Detail of a miniature of Dante and Virgil witnessing the gigantic figure of Dis, with his three mouths biting on the sinners Cassius, Judas, and Brutus, and Dante and Virgil emerging from the Inferno, in illustration of Canto XXXIV, Yates Thompson 36 f. 62v, British Library, London.

Posted by Samantha Hughes-Johnson.