The combined rites practiced by the cult of the Hirpi Sorani (“wolves of Soranus”) in the pagan peninsular countryside and those to honor Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome who were nursed by a wolf, partly explain the name of the Lupercalia, a festival celebrated each February. Though “high Lupercal” is on 15 February, the festival originally began on the Ides, which, in February, is on the 13th. In contemporary times Lupercalia begins today, on 12 February.

Remnants of a Lupercal temple discovered in 2007 15 metres below the Augustan palace were dated to 44 BCE, attesting to the continuity of the festival. But Lupercalia’s best-known attribute is the wolf herself, embodied by the famous Lupa Capitolina.

“Rugged and uncouth though it is, this statue moved my spirit more than all the images that surround it,” wrote German historian Theodor Mommsen when he saw the monument during his first visit to Rome in 1844. In his 1925 treatise on the bronze sculpture French historian Jérôme Carcopino calls the wolf “the most venerable work of Roman archaeology.” Today at her home at the Capitoline Museum in Rome the wolf has many more admirers, visitors whose fingers itch to twirl the regular, S-shaped curls of her mane and to caress her sinewy legs, her elegant tufted paws, and her smooth, distended udders.

The infinitely abundant images of the wolf on Rome-affiliated merchandise seem to increase rather than dilute the potent aura of the statue herself. So what is it about the she-wolf that continues to make her so compelling to those who see her and such an inspiration for writers and artists through the centuries, even to this day? The Lupa Capitolina wields an undeniable appeal through her form alone; yet her formal qualities cannot be disentangled from the defining attributes that have been attached to the statue in the course of history.

Until the past decade (and no matter her actual date of creation, still), Lupa, first of all, reminded us of the rarity of her kind. Few ancient bronzes from Etruria have lasted to the present day because unlike stone, bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) could be fused and reused, and it often was. From statue to cannonball: This was the sad fate of numerous ancient works of art. Therefore we hold ancient bronze statues especially dear because there are so few of them, and these few tell a story of survival against greed and strife.

One of the values associated with the wolf sculpture is her ostensibly Etruscan pedigree; her startling archaic appearance does not need the lost language of her makers to convey the well-known narrative of her role in Rome’s founding. But has Lupa Capitolina been exaggerating her claims of antiquarianism by nearly a millennium? In 2006, archaeological conservator Anna Maria Carruba, who had been a member of the team of researchers restoring the statue in the late 1990s, announced that the symbol of Rome was created in the 7th or 8thCentury or even later.

Carruba’s findings, initially published through the Capitoline Museum itself, have since been questioned by her associates at the same institution. The question about the provenance of the statue is interesting in and of itself, and it does not seem like science will soon provide a definitive answer to them. Statiography and radiography cannot at present be used to exactly date bronze, and Carruba’s finding are based on carbon dating of organic elements associated with the statue (human handling and tiny specks of protein and flora in other words) and on conjecture about the statue’s means of fabrication.

Looking at Lupa

Whenever she was made, Lupa would have been fashioned with the technique called the lost wax (cire-perdu) method. The sculpture began as a detailed, full-size model made out of clay that was then covered with a half-inch thick layer of wax. Some of the details were worked on the wax rather than on the clay; this is true of Lupa’s ears and the crown of curls framing the border between the head and the mane. The model was covered with a thicker layer of clay. The entire piece was then heated so that the wax melted and drained through the holes pierced through the bottom (the holes were later covered with more clay once all the wax was gone). At this point there was a thin hollow space between the clay model and the rough layer of clay that once covered the now “lost” wax. Molten bronze was poured through the small holes into the hollow space. After the bronze hardened the top layer of clay was chiseled away, revealing the bronze statue. Much of the inner clay model was then removed by scraping it out through the bottom openings. With the removal of this inner clay, the bronze statue became hollow and relatively light, rendering it much easier to transport than a marble statue of the same size. Finally finishing touches were applied by working with the hardened metal, and the resulting artwork was an ostensibly unique and unrepeatable product – theoretically, no other replicas could be made from the original model.

The expressiveness of Lupa’s body is extraordinary. The wolf looks ferocious: Her eyebrows raised in bronze imitation of the lighter coloring visible in live wolves, are contracted and expressive; her ears are pricked; her gaze intent, penetrating – individualized, even, through the precision of its expression. Her facial muscles are tense, and the vein running from her nose to just under her right eye is visibly swollen. On her surface, the Lupa Capitolina blends a precise attention to the reality of live wolves with a certain respect for representational convention regarding sculpted animals. This wolf is rigid and expressive, at once static and poised to pounce. The flexed muscles of the wolf, her attentive gaze, her wrinkled brow, all elicit a connection between human and animal, between artwork and viewer. The wolf’s gaze makes the statue’s visible emotions something with which viewers can immediately identify: She looks attentive and ready, protective and fierce. The “unusually complex expression in the face of the wolf,” as artist Stanley Horner described his own aesthetic reaction to the Lupa Capitolina “is more devastating than the Mona Lisa; it can smile and snarl in the same countenance, whichever I wish to project upon it.”

The Renaissance addition of the Twins

The manufacture of the free-standing bronze twins set a higher technical challenge than the production of low relief scenes like those of the reliquary doors designed by the Pollaiuolo brothers Antonio and Giuliano, and there is good reason to think that whoever was directly responsible for the commission – whether Giuliano or another member of the Sistine court – looked to Florence (where the Pollaiuolos were from) for someone with the commensurate skills in bronze casting. Stylistically the treatment of the children’s bodies is generically Donatelloesque; the rounding out of male musculature in the torso, the soft peaks of the nipples and the comically pendant buttocks are like those of Donatello’s bronze David. Vassari related the plump forms of the bronzes to the infants Cain and Abel in Antonio Pollaiuolo’s drawing of Eve in the Uffizi while Charity’s child on the reverse of the Uffizi panel offers a precedent for a slightly stockier, suckling baby, with chubby bent legs. The rather awkward (in terms of the comfort of posture for the babies) setting of the heads on the necks also brings to mind the foreshortening of the left-hand angels of the Staggia Elevation. But the problem remains that the unusual nature of the Roman task – to produce free-standing sculptures that would complement a revered ancient bronze – limits the usefulness of such comparisons.

The addition of the twins helped if not to fix, then to control, the ancient work’s meaning. From a fearful symbol of judicial authority, the wolf was reinvented as an appropriately beneficent source of miraculous succor to Rome ancient and modern.

Jérôme Carpocino, who was so moved by the statue of the wolf, insisted that the myth of the Capitoline Wolf did not yet exist when the bronze wolf was produced: The story of Romulus and Remus dates back to the second half of the fourth century BCE whereas the bronze was cast in the course of the fifth. In any case the Lupa is not a comfortable object for those in search of authenticity. It is physically available to us today as a material bridge to a lost world, a bygone era. A large part of Lupa’s impact on her viewer is due precisely to her vivid aura of authenticity, undiminished and perhaps even increased by her frequent reproduction. The legendary she wolf may be historically distant but she is physically even immediately present. The symbolic values of the Capitoline Wolf remain untouched by the progress of knowledge. They live on and in fact are nourished by ideals belonging to a metahistorical perspective.

Reference: Anna Maria Carruba and Lorenzo De Masi. La Lupa capitolina: un bronzo medievale. Rome: De Luca editori d’arte, 2006.

Capitoline Wolf: c.500-480 BCE or c. 1300 CE? Etruscan or Medieval?

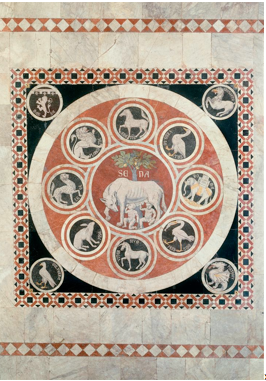

Gothic She-Wolf with the Symbols of the Allied Cities inlaid floor work from the Duomo of Siena. The twins-facing posture of the wolf also mirrors the encircling concentric frames.

A side view of the sculpture at the Capitoline Museum in Rome shows how the wolf is best experienced by moving around the bronze.

Capitoline Wolf with figures of Romulus and Remus (possibly created by Antonio del Pollaiuolo) added c. 1472.

She-Wolf, Romulus and Remus. Silver didrachm, 269-266 BCE, shows an active trio of figures.

Detail of hair on the head of Lupa.

Further Reading: Jérôme Carcopino. La louve du Capitole. Paris: Société d’ed. “Les belles lettres,” 1925.

Francis D.Klingender, Animals In Art And Thought To The End Of The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Mass., M.I.T.: Press, 1971.

Carol C. Mattusch “In Search of the Greek Bronze Original.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes, Vol. 1, The Ancient Art of Emulation: Studies in Artistic Originality and Tradition from the Present to Classical Antiquity(2002), pp. 99-115.

Dietmar Popp. “Lupa Senese. Zur Inszenierung Einer Mythischen Vergangenheit in Siena (1260-1560).” Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft, Kunst als Ästhetisches Ereignis (1997): pp. 41-58.

Emeline Hill Richardson, “The Etruscan Origins of Early Roman Sculpture.” Memoirs of the American academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes, Vol. 21, The Ancient Art of Emulation: Studies in Artistic Originality and Tradition from the Present to Classical antiquity (2002), pp. 75-124.